This page describes conventions and best practices applicable to the Fedora Git repository.

| Table of Contents |

|---|

| Note |

|---|

Two things you should never do in git:

In general, the preferred workflow is:

|

Overview of the Git Lifecycle

Git allows a developer to copy a remote subversion repository to a local instance on their workstation, do all their work and commits in that local repository, then push the state of that repository back to a central facility (github).

Bearing in mind that you will always being doing your work and commits locally, a typical session looks like this:

git clone git@github.com:fcrepo/fcrepo.git && cd fcrepo

Get a copy of the central storage facility (the repository).

git branch fcrepo-756

Create a local branch called "fcrepo-756".

git checkout fcrepo-756

Create a local copy of the branch from master if it doesn't exist, make it your active working branch.

Now, start creating, editing files, testing. When you're ready to commit your changes:

git add [file]

This tells git that the file(s) should be added to the next commit. You'll need to do this on files you modify, also.

git commit [file]

Commit your changes locally.

Now, the magic:

git push origin fcrepo-756

This command pushes the current state of your local repository, including all commits, up to github. Your work becomes part of the history of the fcrepo-756 branch on github.

git push is the command that changes the state of the remote code branch. Nothing you do locally will have any affect outside your workstation until you push your changes.

git pull is the command that brings your current local branch up-to-date with the state of the remote branch on github. Use this command when you want to make sure your local branch is all caught up with changes push'ed to the remote branch.

Some useful terms

master: this is the main code branch, equivalent to trunk in Subversion. Branches are generally created off of master.

origin: the default remote repository that all your branches are pull'ed from and push'ed to. This is defined when you execute the initial git clone command.

unpublished vs. published branches: an unpublished branch is a branch that only exists on your local workstation, in your local repository. Nobody but you know that branch exists. A published branch is one that has been push'ed up to github, and is available for other developers to checkout and work on.

fast-forward: the process of bringing a branch up-to-date with another branch, by fast-forwarding the commits in one branch onto the other.

rebase: the process by which you cut off the changes made in your local branch, and graft them onto the end of another branch.

Line endings

All text files in must be normalized so that lines terminate in the unix style (LF). In the past, we have had a mixture of termination styles. Shortly after the migration to Git the master and maintenance branches were normalized to LF. Please do not commit files that terminate in CRLF!

...

- (master)

git pull - (master)

git commit -m "A" - (master)

git pull(results in a silent, automatic merge commit P1 since this pull is not fast-forward) - (master)

git pull(results in another silent, automatic merge commit P2 since this pull is not fast-forward) - (master)

git commit -m "B" - (master)

git pull(Yet another merge commit P3) - (master)

git push(The repository master now is identical to his local master)

...

In this graph, Harry's local commits and pull merges appear to have occured occurred in master. Tom's commits (which were always pushed immediately to master) appear to have occured occurred in a separate branch. In a way, this is actually an accurate representation of what has occurred. Harry made some commits in his master branch, merged in changes from a another branch three times, then replaced the repository master with his own.

...

Let us use the same Tom, Dick, & Harry example, except with Harry performing his development in a local, non-published branch. In this example, harryHarry's workflow looks like the following:

- (master)

git pull - (master)

git branch harry_branch origin/master --track - (harry_branch)

git commit -m "A" - (harry_branch)

git pull(results in a silent, automatic merge commit P1 since this merge is not fast-forward) - (harry_branch)

git pull(results in a silent, automatic merge commit P2 since this merge is not fast-forward) - (harry_branch)

git commit -m "B" - (master)

git pull(Is fast-forward. No merge commit created) - (master)

git merge harry_branch(results in an explicit merge commit P3} - (master)

git push(The repository master now is identical to his local master)

...

As is evident, the github history graph is still complex, but perhaps more "intuitive" in the sense that it preserves the fact that commits 1,2,3,4,5 and 6 had been published in master, and that Harry's commits A and B occurred in some other branch. Harry's pull merges are also preserved - but this time it is clear that changes (commits 4 and 5) were propagated from master into his own branch during the pull/merge, and that he merged his branch back into the published master at the end.

With this technique, pushing the local branch (harry_branch) to the repository occasionally would make no difference, and would be safe. This pattern has an identical end result to maintaining a published fcrepo-XXX feature/bug branch, and merging it with master in the end.

Development in a local branch with rebase

Development in an unpublished local branch, and using git rebase instead of pull or merge to update the local branch with changes to master is also a valid pattern. This technique results in the elimination of the local branching history, and rather than a final merge applies all local commits in sequence to the end of the current master. This may be used when the local branch and merge history is unimportant or unnecessary (perhaps bad luck - while making two trivial local commits, somebody happened to push master in the meantime).

It is important to never rebase a published branch if you intend on ever pushing that branch again. As a safety, Git will refuse to push a branch that has had its history re-written with rebase. Although it is possible to force the changes through with --force, never do that!

Let us use the same Tom, Dick, & Harry example, except with Harry performing his development in a local, non-published branch, with occasional rebasing to track the changes in master.

- (master)

git pull - (master)

git branch harry_branch origin/master --track - (harry_branch)

git commit -m "A" - (harry_branch)

git fetch; git rebase origin/master(Modifies Harry's A commit so that it appears to have occurred after all changes that have been imported from master) - (harry_branch)

git fetch; git rebase origin/master(Modifies Harry's A commit so that it appears to have occurred after all changes that have been imported from master) - (harry_branch)

git commit -m "B" - (harry_branch)

git fetch; git rebase origin/master(Modifies Harry's A and B commits so that they appear to have occurred after all changes that have been imported from master) - (master)

git pull(Is fast-forward. No merge commit created) - (master)

git merge harry_branch(fast-forward. Does not result in merge commit) - (master)

git push(The repository master now is identical to his local master)

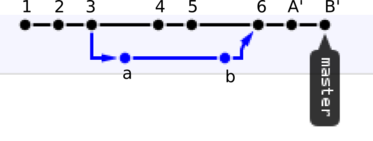

This results in a very simple history. Since rebase operations result in new commits at the end of a tree, Harry's a and B commits were transformed into A' and B', which could be simply applied almost as a patch directly to the end of master in a fast-forward merge. The end result is exactly the same as if Harry were to git cherry-pick the two commits from his harry_branch onto master - they both result in new commits at the tail of a branch.